The following research piece entitled Cities for Children: A Case Study of Refugees in Towns – Islamabad, Pakistan, was first published by the Refugees in Towns project of the Feinstein Centre, Tufts University, September 2019. It is a unique reflective case study drawing upon personal and professional experiences, exploring the lived reality and education-based challenges of Afghan refugee children in Islamabad.

CITIES FOR CHILDREN: A CASE STUDY OF REFUGEES IN TOWNS, ISLAMABAD, PAKISTAN

Author: Madeeha Ansari

INTRODUCTION

Over the past four decades, Pakistan has experienced several waves of refugees due to recurring conflict in neighboring Afghanistan, as well as repeated internal displacement caused by complex emergencies within the country. It has hosted one of the largest refugee populations in the world—4 million at its peak—and in spite of efforts to facilitate return, is still home to about 1.4 million registered refugees.[1]

Although designated “refugee villages” were created by aid agencies to accommodate large numbers of refugees, many chose to live and work in cities. The capital city of Islamabad has seen refugee populations enter and leave multiple times since the 1980s. As of June 2018, the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) had registered 33,286 Afghan refugees in Islamabad Capital Territory (ICT).[2] However, it is widely recognized that the numbers of unregistered refugees as well as internally displaced persons (IDPs) are far greater.[3]

This report looks at the integration experiences of Afghan refugees in slum areas of Islamabad, particularly in the neighborhoods of F-11 and I-10 (see Figure 2). Drawing from my own experience working with street-connected children, it presents stories to illustrate the obstacles to integration for those lacking formal legal status, especially in terms of education. Finally, it highlights good practices that would improve the refugee experience of education, including wellbeing as a consideration for mobile children in cities.

The Author’s Position in Pakistan and Experiences Researching this Report

I was born and raised in Islamabad, living there until the end of high school and then returning as a young professional. My mother tongue is Urdu, the local language that many refugees, after protracted displacement, now speak or understand. I was part of the first generation “belonging” to the relatively new city. I watched it grow from a quiet, contained capital to one experiencing the challenges of rapid urbanization. During this time, I have observed how perceptions of Afghan refugees have evolved, and how these perceptions have affected their everyday lives.

Islamabad is a hub for development in Pakistan, with agencies across the aid spectrum. After returning from my undergraduate studies, I started working concurrently for a think tank and a small trust called Jamshed Akhtar Qureshi Education Trust operating a network of non-formal, open-air schools in multiple slum areas. This meant stepping outside my comfort zone and becoming immersed in the lives of Afghan communities in urban and peri-urban settlements: the way they interacted with other communities; the options they had in terms of accessing services; and the barriers to integration.

I was able to explore—and formally articulate—my interest in education for forcibly displaced communities during my graduate studies at The Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy, Tufts University and later while setting up the non-governmental organization (NGO) Cities for Children. This document is a cumulative result of the academic and professional experiences related to education for refugees.

For more on the methods used for this case report, continue to Appendix A.

[1] See UNHCR country pages, https://www.unhcr.org/pakistan.html, https://unhcrpk.org/who-we-are/.

[2] See UNHCR operational portal, https://data2.unhcr.org/en/country/pak.

[3] While this is widely accepted as true in the city, the unregistered are not in official counts and they move around, so exact numbers are not available.

LOCATION

Islamabad is situated in South Asia, a region with highly porous borders and large movements of people, settling and resettling throughout Afghanistan, India, Iran, and Pakistan as conflicts and economic opportunities ebb and flow. Click the map to learn more about the region, and read more RIT cases from the region.

Continue to the appendices for more information on the methods used for this report, and for background on refugees in Islamabad and Pakistan.

A NOTE ON TERMINOLOGY

“Refugees” as used here includes unregistered families, those having Proof of Registration (PoR) cards, as well as those who have been able to access Afghan Citizen cards since 2017. Afghan Citizen cardholders are no longer classed as refugees/persons of interest by UNHCR, as they are seen as migrants seeking education and livelihoods. “Refugees” is used as an umbrella term in this report because most of these individuals came to Islamabad before 2017, and while the new PoR card offers some legal protection, the report findings apply to most Afghan people who live in urban poverty. The report does not address the integration issues of IDPs, although recurring internal displacement is a challenge for Pakistan.

A NOTE ON SCOPE

The report is limited to a discussion only of the integration experiences of Afghan refugees living in urban poverty, primarily in slum settlements. Many other Afghan refugees live in middle- or high-income households and have had different experiences of the city.

MAPPING THE REFUGEE POPULATION

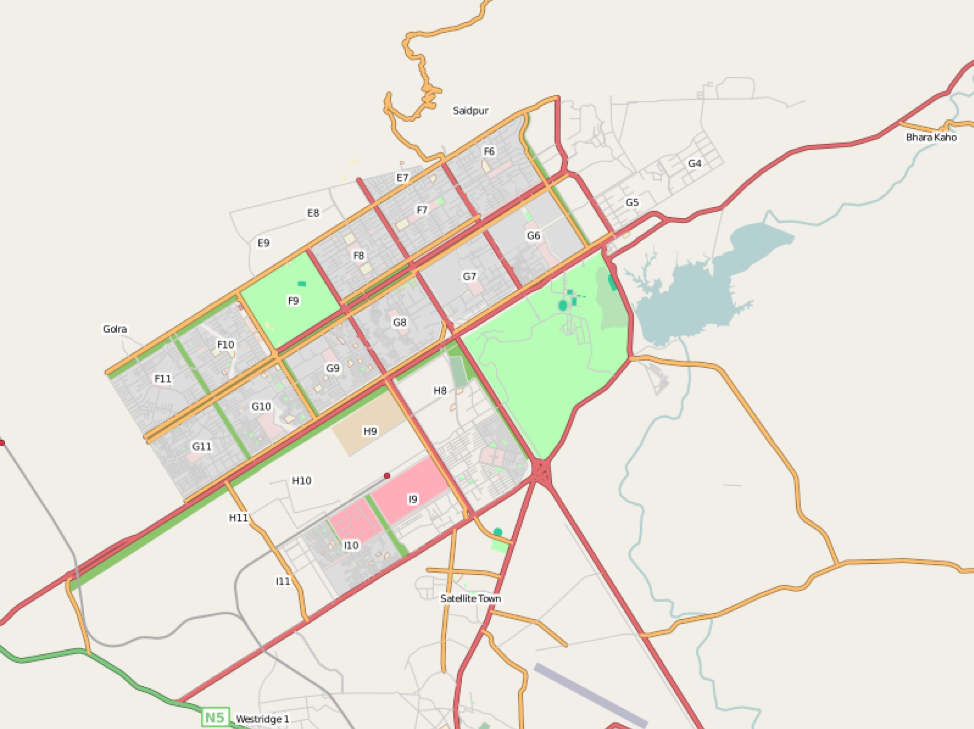

Islamabad was constructed as a purpose-built capital city in the 1960s, when the seat of government was moved from the port city of Karachi. It is laid out in a grid structure, with each developed “sector” having schools, markets, and green belts. Slum settlements are not recorded on the official maps but have sprung up in existing green belts.

Specific points of interest for refugees include:

Ministry of States and Frontier Regions (SAFRON) and UNHCR head office;

The head office of the National Database and Registration Authority (NADRA), which holds the database for identity cards;

Proof of Registration (PoR) Card Modification Centre (PCM) in Rawalpindi, where PoR cards can be modified/renewed and births can be registered;

Offices of international humanitarian and development organizations coordinating with UNHCR to offer services, e.g., Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit GmbH (GIZ) and ICMC. Among other services, ICMC offers safe shelter for individuals referred by UNHCR, including survivors of gender-based violence and children at risk;

Legal assistance project office of the Society for Human Rights and Prisoners’ Aid (SHARP), a local implementing partner for UNHCR.

Two areas of interest in terms of livelihoods are:

F-7 Markaz, where refugees can be small vendors selling “Afghani chips” or jewelry as well as larger shop-owners;

Sabzi Mandi, a wholesale fruit and vegetable bazaar.

While services have clustered in downtown Islamabad (upper right), residences have sprawled into informal settlements and “former neighborhoods” (shaded blue). Map by author. Base map imagery © Google 2019. Click map to enlarge.

Some neighborhoods that were previously densely populated by Afghan families have been highlighted on the map. One was known as the “Afghan Basti” in Sector I-11, close to the Sabzi Mandi market (highlighted on the map in blue). This neighborhood was demolished by municipal authorities in 2015.[4] Another is the green belt of Sector I-12, a recognized settlement where 3,000 Afghan individuals were relocated with the support of UNHCR in 2009. According to interviews with NGO staff, one result of ongoing repatriation efforts[5] is that there are few openly majority-Afghan settlements. While many families have relocated to Afghanistan, others have scattered across the city.

[4] For this demolition, the Capital Development Authority (CDA) cited a court-authorized drive against illegal settlements that allegedly bred crime and terrorism—allegations for which evidence was not provided.

[5] See Appendix B, “Refugees in Pakistan,” for more details.

THE HOST POPULATION AND INTEGRATION

During the Soviet-Afghan war (December 1979 to February 1989), Pakistanis welcomed Afghans with hospitality and a sense of kinship. Particularly in the mountainous northern territories, refugee families were able to easily integrate into Pashtun society due to a shared language and culture.

Given its geographical proximity to the northern province of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP), Islamabad was the second-most significant urban center to receive refugees after Peshawar. However, unlike KP, Islamabad is ethnically diverse. Over the decades, there has been a shift in the perceptions of Pakistanis towards refugees. Attitudes have become reserved or even hostile as host communities began to see the spillover effects of the neighboring conflict on the local economy, culture, and polity.

In Pashtun culture, the concepts of “Melmastia” and “Nanawati” represent hospitality and asylum, and are among the six basic principles of the social code, Pashtunwali. When Afghans first entered Pakistan they experienced “Melmapana”—open hospitality extended to those who arrive at the doorstep without first being extended an invitation.

While some in urban society do hold more empathetic views towards people of Afghan origin, today, many Pakistanis in Islamabad link refugee presence with the proliferation of Kalashnikovs (rifles), narcotics, and violent extremism. They blame regional politics for Pakistan becoming a route for the regional illicit opium and heroin trade. The pressures of hosting a large refugee population, in spite of substantial international aid, have also become a source of tension. National government-level politics have shaped attitudes too; in recent years, relations between the Afghan and Pakistani governments have deteriorated, and there has been a push for refugee return. Current public attitudes are reflected in the populist reaction to Prime Minister Imran Khan’s announcement in September 2018 of the possibility of citizenship for Pakistan-born refugees. One step towards better integration in 2019 has been financial inclusion; for the first time, Afghan refugees holding PoR cards have been able to open bank accounts. However, their status is still insecure. In the face of public outcry and political backlash, the issue of citizenship has not yet been taken up in Parliament.[6]

[6] For more on identity, see Appendix B, “Refugees in Pakistan.”

A FOCUS ON EDUCATION

Education is a fundamental right, as set out in the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. For children whose lives are disrupted by emergencies and displacement, education can be a source of stability.[7] Education serves a protective function by meeting cognitive and psychosocial needs, and helps young people access livelihoods and pathways to a better future.[8]

“The State shall provide free and compulsory education to all children of the age of five to sixteen years in such manner as may be determined by law.” Article 25a, Constitution of Pakistan (2010).

The government of Pakistan has committed to providing education for all.[9] There are several categories of primary and secondary schools for Afghan children in Pakistan:

Registered public schools;

Registered private Pakistani schools (for middle-high income households);

Private Afghan schools registered with the Ministry of Education Afghanistan, through the Afghan Embassy/Consulates (for middle-high income households);

Refugee village schools supported by UNHCR;

Non-formal schools, including those run by non-profits;

Madrassahs (religious schools).

However, there are barriers to education for both Pakistani and Afghan children, and Pakistan has the second-highest population of out-of-school children in the world. This is because of lack of adequate school facilities and trained teachers. For Afghan refugees, there are numerous barriers in accessing education, particularly for those who are unregistered. As a result, according to UNHCR, the literacy rate of Afghans aged ten and above is 33%.[10]

UNHCR has a range of education programs for refugees in the 54 refugee villages, through which 57,000 refugee children access primary-level and sometimes secondary-level education.[11] It also provides tertiary-level scholarships to 400 Afghan refugee youth through the Albert Einstein German Academic Refugee Initiative (DAFI).[12]

Shoes arranged outside informal school. Click the photo to expand.

Compared to the designated refugee villages, the urban educational experience is different for the majority of refugees. Non-camp refugees and IDPs often lack access to mainstream schooling and rely on non-formal or religious schools. UNHCR’s new education strategy aims to address this gap by extending support for public schools in areas of high refugee density.

However, there are barriers to education for both Pakistani and Afghan children, and Pakistan has the second-highest population of out-of-school children in the world. This is because of lack of adequate school facilities and trained teachers. For Afghan refugees, there are numerous barriers in accessing education, particularly for those who are unregistered. As a result, according to UNHCR, the literacy rate of Afghans aged ten and above is 33%.[13]

[7] See Kirk, 2011.

[8] See Dryden-Peterson, 2011.

[9] From 2010 onwards, Article 25a of the Constitution affirmed the right to free and compulsory education for all children in Pakistan regardless of origin. In November 2012, the Islamabad Capital Territory passed a bill guaranteeing the fundamental right to free and compulsory education to every child regardless of sex, nationality, or race.

[10] UNHCR Pakistan, 2017.

[11] UNHCR Pakistan, 2018.

[12] Ibid.

[13] UNHCR Pakistan, 2017.

EDUCATION AND IDENTITY

Legal status affects refugees’ ability to apply for educational opportunities. Even after decades of living in Pakistan, there are no laws for refugees, and the reliance on temporary international agreements makes their status insecure. The citizenship status of the second generation is still “Afghan,” and there are no pathways to Pakistani citizenship.[14] As a result, large numbers of unregistered refugees live under the official radar in Pakistan’s cities, with little access to formal housing, sanitation, and education services.

The following stories and testimonies from young people illustrate the challenges for refugee education and integration in informal settlements or “katchi abadis.”

[14] See Appendix B “Refugees in Pakistan,” sub-section on “Integration and attitudes of host population” for more details.

A CHILDHOOD STORY

As a child in the 1990s, I had regular contact with refugees in everyday life. At the time, their presence was simply accepted as a reality of the city’s businesses and culture. In the markets, there were shops selling Afghani carpets and Afghani jewelry, silver/metallic accessories inlaid with semi-precious stones like lapis lazuli. “Afghani chips” were crinkle-cut potato fries sold at street stalls in small newspaper bags, with signature spices and chutney. An Afghan vendor sold Afghani chips at my high school and was a rival to the official canteen. One day, the boys in my class came back with their trigonometry problems solved during the lunch break. It turned out that the man selling fries had been a professor at a university in Kabul. His degree was not recognized in Pakistan. Like this Afghan professor, refugees often lose their national-level certification when they cross into a host country. Unless provisions are made to recognize this, they often have to start from scratch in terms of livelihoods, education, and identity.

A “katchi abadi,” or slum settlement. Click the photo to enlarge.

EDUCATION INTERRUPTED

Many families have moved between Pakistan and Afghanistan several times, disrupting their children’s education. Ali Khan[15] started out in the Pehli Kiran non-formal education system, which he attended until Grade 4 (age nine or ten).[16] Then his family moved back to Afghanistan, and he was able to continue classes in Pashto and Farsi, the local languages. When his family moved back to Pakistan again, Ali needed to repeat some classes, again in the non-formal system as opposed to a mainstream school. After completing primary education in English and Urdu, he was lucky to be enrolled in the local government school. There he tested well, and instead of Grade 6, was offered a place directly in Grade 9.

Ali’s experience of interrupted education followed by an accelerated non-formal program places him among the more fortunate. Many whose schooling is disrupted are more unlikely to return to school, especially if they move between academic systems in different languages. Schools in Afghanistan recognize the Pakistani system of education for children who are repatriated, but a transition back into a Pakistani school is not as straightforward.

[15] Pseudonym.

[16] Actual ages in grades may vary considerably.

GENDER AS A BARRIER

According to UNHCR, in Punjab (and ICT) only 20% of school-going-aged girls were enrolled in schools.[17] Afghan girls face a host of practical and cultural constraints in accessing schooling, including lack of gender-segregated facilities and trained female teachers. Distance is also a factor; if girls have to travel, even in densely populated urban contexts, they often do not get permission to go from male family members. One girl from an Afghan family provided written testimony about her experience:

Female students leaving an open-air Pehli Kiran School. Click photo to enlarge.

I am the first girl in my family to study further. When I passed Class 5 in PK-4, my brother did not accept that I would study in another school. The teachers of PK-8 talked to the administration to add Class 6 to the school. When Big Madam agreed, the teachers came to our house to talk to my brother. My brother accepted, and I am now studying in Class 6 in PK-8. — Gul Bibi[18]

Many girls like Gul Bibi are forbidden to access a mainstream secondary school by a male family member. Gul Bibi continued her education through an extension of the non-formal school in her community after a mobilization effort by staff. In most situations, these are not options, and girls fall out of the educational system.

[17] UNHCR Pakistan, “Mapping of Education Facilities,” 14.

[18] Pseudonym.

ECONOMIC CONSTRAINTS

Even when access to educational services exists, the economic pressures families in katchi abadis experience lead to high dropout rates—as early as age eight or nine—when children start working. Afghan children in katchi abadi neighborhoods work to pick through trash, particularly to find and sell metal items, or as fruit and vegetable vendors. In one school, attendance dropped on Thursdays because the boys would be helping their fathers sell produce in the local bazaar. A smaller number drop out after gaining apprenticeships at local mechanic workshops rather than continuing to secondary school. Erratic attendance impacts learning outcomes, which negatively affects motivation to attend school.

RISKS FOR THE UNREGISTERED

EXPLOITATION AND HARASSMENT

One of the Pehli Kiran schools in Sector I-10 served undocumented refugees in a mud settlement hidden from view from the main roads. The school shed served multiple community purposes, including weddings. The legal status of the families meant that they were constantly at risk of exploitation as well as harassment. A local cleric used his connections with the police to threaten the community and sought to expand his mosque by encroaching on land occupied by the school shed. In spite of this pressure, a Jirga meeting was convened.[19] All the men of the community attended and collectively decided in favor of the school. The story illustrates the high value placed on education by underserved refugee communities and the obstacle that police harassment presents to integration. Fear of harassment was cited as a major reason why Afghan families opted to return to Afghanistan in 2016.[20]

[19] A Jirga is a traditional gathering of elders to make decisions by consensus based.

[20] Conversation with UNHCR staff.

TENSION WITH MUNICIPAL AUTHORITIES

Lack of legal status means refugee in slum areas typically lack housing security, even though settlements may have existed in the same location for decades. In recent years, there has been a crackdown by the Capital Development Authority (CDA). In February 2014, a court ordered municipal authorities to clear the slums in Islamabad. A month later a double suicide bomb attack in the district courts increased the government’s motivation to act; no evidence of a link was provided, but slum areas were perceived to be unregulated havens harboring terrorists. In April 2014, the I-10 settlement where the community had voted in favor of keeping the school open for their children was demolished by the CDA. The children and their families were given no alternative housing and were dispersed to different parts of the city.

View of a “katchi abadi,” or slum settlement. Click photo to enlarge.

Slum demolition continued through 2015. However, during this time an unprecedented political movement gained foothold in the city. The All Pakistan Alliance for Katchi Abadis emerged as a platform for organized protest by inhabitants of informal settlements across Islamabad. Brought together by the efforts of the left-wing Awami Workers’ Party, this Alliance garnered enough attention to bring an official halt to demolition at the end of 2015. Currently, tensions with municipal authorities are continuing for slum-dwellers of different ethnicities.

BUREAUCRATIC OBSTACLES

Education in Pakistan is a right, not a privilege, and Afghan children should be able to access education without facing bureaucratic hurdles. This has not been their experience. Ali Khan[21] was determined to continue his education in spite of the challenges of urban poverty and disruption caused by migration:

In the morning, I would work as a laborer and go to school in the evening. My father was very poor. He could not afford my education…After passing Class 5, I wanted to study more and continue education in a government school. However, things were very bad then, and I faced many difficulties in gaining admission. When my father went to get me admission in a government school, they said we can’t give you admission without a No Objection Certificate (NOC). I was told to go to the Federal Directorate of Education (FDE) to get a NOC, then I would be able to get admission. In fact, they sent us to D block SAFRON Ministry and said we had to get an Afghan Citizen card and a letter from the school where you first got education. The school prepared all the relevant documents and (a teacher) also went to the FDE, Interior Ministry, SAFRON Ministry, and Police Foundation with me to get me a NOC and admission.

This experience was at a time when the government and UNHCR were encouraging registration for Afghan Citizen cards. To go through the steps of obtaining an additional NOC is time-consuming and can be a prohibitive factor for families for whom lost time equates to lost income. The right to education for all exists on paper, but there are significant bureaucratic hurdles for Afghan children trying to enter oversubscribed mainstream schools. [22]

[21] Pseudonym.

[22] In Islamabad, UNHCR researchers working on education mapping in 2017 were not able to gain access to public schools—even telephonically—without the approval of the Federal Directorate of Education. This approval was not received in spite of several follow-up attempts (UNHCR Pakistan, “Mapping of Education Facilities,” 12).

CITIES FOR CHILDREN

Even when refugee children from slum communities gain access to schools, barriers to learning remain. They lack support at home due to time, knowledge, or resource constraints on the part of parents. The chronic stress of urban poverty takes a toll on all family members, with children experiencing neglect and often emotional and physical abuse. These factors affect their performance as well as behavior at school. During a workshop of the NGO Cities for Children that brought together mental health professionals and teachers, the teachers discussed their troubles dealing with behavioral difficulties, especially without corporal punishment. Boys from Afghan and Pashtun communities often demonstrated aggressive or hyper-masculine behavior, and the only strategy the teachers saw for dealing with it was violence. There was a problem of school refusal too: children sometimes ran away from class, particularly if there were attempts to discipline them.

Cities are challenging places for children, and schools should represent an opportunity for integration and for building the resilience of street-connected children. The teacher can be an important attachment figure, supporting refugee students, and school-based programs involving socio-emotional learning can improve behavior and academic performance, while also promoting positive mental health.[23]

LOOKING AHEAD

LEGAL RECOGNITION

Recent efforts to register births and provide Afghan families with the chance to claim an identity have had some impact in Pakistan. Legal recognition of status entails recognition of human rights and of children’s right to education. However, for unregistered families to have the confidence to come forward, they need the reassurance that they can retain the choice to live in a country that many have come to call home. For the second generation, it is the only home that they have known.

EDUCATION AND INTEGRATION

Urban settlements in Islamabad are loosely organized according to ethnicity, as people from similar backgrounds tend to cluster together. Within the open-air schools, Afghan, Pakistani, Pashtun, and Punjabi children are sometimes divided along linguistic lines, with students speaking the same language preferring to sit together. Education can be a powerful force for integration. It provides the opportunity for host and refugee children to interact as peers and share the experience of learning and growing. Play-based interactions and learning within the school space can additionally aid integration by blurring the lines drawn by ethnicity and class.

A curriculum designed to support integration can promote the ideals of peace and tolerance, as well as an appreciation for diversity. It can challenge notions of male dominance and promote better gender equity. Teaching might be arranged such that students are not partitioned by linguistic group, to allow normalization and social cohesion to build. Access to secondary and tertiary education can further provide adolescents and young people with opportunities to contribute positively to their households and to participate in broader society.

A USEFUL EDUCATION

For Afghan children facing the challenges of urban poverty in Islamabad, unhindered access to quality education would provide the opportunity to overcome vulnerabilities and to build true durable solutions for their families. Skills that would be useful to focus on as part of education for both documented and undocumented Afghan children include the following:

Language skills. Fluency in Urdu helps overcome barriers to local communication, and English is the language of social mobility. English skills are particularly useful if young people return to Afghanistan. Languages are offered in most schools but can be challenging for children to learn if parents are not fluent. Language barriers can affect their performance in all subjects.

Vocational skills. Many children living in katchi abadis are pushed to choose between work and school at an early age, and time spent at school is seen as loss of income. The perceived and actual value of time spent at school would be higher if they were able to gain access to technical skills:

“For us Afghan children, along with education it is important to learn skills, because we are from poor households. By using these skills, we can increase our income and improve our economic situation, e.g., through computer courses, driving, and electrician courses, etc. If Afghan families go back, then along with education it is important for them to have skills they can use and contribute to the prosperity of their country.” — Ali Khan

Socioemotional skills. Beyond literacy and numeracy, children in urban poverty also need spaces where they can gain respite from daily stressors. There is a strong case for creating play-based programs that build socioemotional skills for children, as well as their resilience to cope with difficult circumstances.

One example from Cities for Children is the “Happy Hoods” project, which equips local volunteers to build socioemotional competencies like self-awareness, self-management, social awareness, and relationship skills. The programs involve discussion and extracurricular activities, based on the premise that “happy memories build resilience” for vulnerable children. The pilot programs were conducted with a school and drop-in center for migrant children, with the aim to scale up to reach refugee populations. At the end of the pilot, staff reported improvements in confidence and interpersonal skills, with shy children coming forward and speaking up, and higher general motivation to attend school.

CONCLUSION

The integration of Afghan refugee children in Islamabad will continue to face obstacles, including police and municipal government harassment, financial barriers, insecure housing, and limited legal protections. However, educational efforts that improve language abilities, build vocational skills, support connections across populations, and build social skills may help improve wellbeing and integration.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I would like to acknowledge the students and team from the Pehli Kiran Schools, in particular Managing Trustee Sabira Qureshi and Operations Coordinator Ghazanfar Ali for support in the research; Wali Kandiwal for his comments; and Usama Khilji, Director of Bolo Bhi, for his feedback.

Madeeha Ansari

Madeeha@www.citiesforchildren.co

Madeeha is currently spearheading the non-profit Cities for Children, which seeks to protect the “right to a childhood” for street-connected children—the right to read, play, and feel safe. Cities for Children partners with other organizations to provide services to children from refugee, internally displaced, and migrant communities on the margins of urban society. Previously she worked with open-air schools for mobile children, Save the Children, and the Malala Fund. She has written on issues of forced migration for leading newspapers and think tanks in Pakistan, as well as for international blogs. Madeeha completed her master’s degree as a Fulbright scholar at the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy, Tufts University and earned her undergraduate degree at the London School of Economics.

REFERENCES

Dryden-Peterson, S. (20110). “Refugee Children Aspiring Toward the Future: Linking Education and Livelihoods,” in Educating Children in Conflict Zones: Research, Policy and Practice for Systemic Change, edited by Sarah Dryden-Peterson and Karen Mundy, 85–100. New York: Teachers College Press.

INEE. (2016). “Background Paper on Psychosocial Support and Social and Emotional Learning for Children and Youth in Emergency Settings.” Available at: http://s3.amazonaws.com/inee-assets/resources/161114_PSS_SEL_Background_Paper_Final.pdf

Kirk, J. (2011). “Education and Fragile States,” in Educating Children in Conflict Zones: Research, Policy and Practice for Systemic Change, edited by Sarah Dryden-Peterson and Karen Mundy, 15–32. New York: Teachers College Press.

UNHCR Pakistan. (2017). “Mapping of Education Facilities and Refugee Enrolment in Main Refugee Hosting Areas and Refugee Villages in Pakistan.”

UNHCR Pakistan. (2018). “Fact Sheet.”

APPENDIX A: METHODS

For this report, I relied on my personal and professional experiences while working for non-formal schools in slums around Islamabad, and while setting up Cities for Children, a non-profit to address the wellbeing of street-connected children. The report draws on personal, in-depth contact with approximately 250 refugee children at two non-formal schools from the Pehli Kiran School System (PKSS); a focus group discussion with 15 mothers from a slum community; and written responses of 4 pupils to a questionnaire. I would like to acknowledge the cooperation of the schools’ management team in facilitating the written responses.

In order to obtain a fuller picture of available services, I also conducted key informant interviews with the following people:

A staff person formerly at the International Catholic Migration Commission (ICMC);

Two representatives from UNHCR Pakistan;

Two representatives from the International Rescue Committee.

To compare the experiences of non-camp versus camp refugees, I talked to an Afghan researcher who was educated in a refugee village. Information about practical challenges was obtained from informal conversations with staff from the Society for the Protection of the Rights of the Child (SPARC) as well as staff and teachers from the Pehli Kiran school system (PKSS). I gleaned insights about the host population from informal conversations with residents from Islamabad in group settings, as well as from social media responses to policies for Afghan refugees.

APPENDIX B: REFUGEES IN PAKISTAN

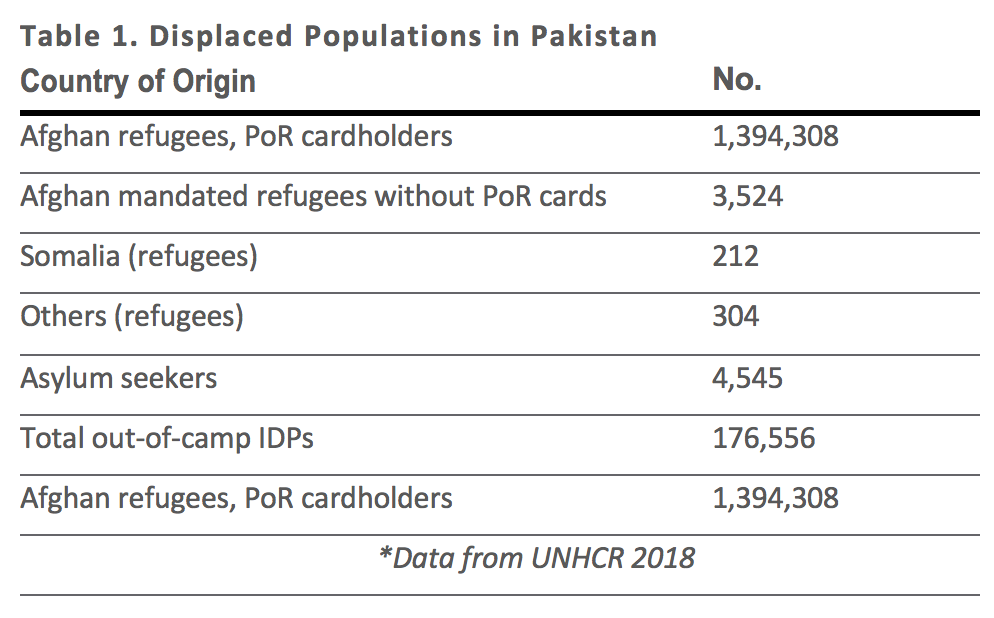

The largest ethnic group of refugees in Pakistan is of Afghan origin. Historically, Pakistan shared a porous border with neighboring Afghanistan—the Durand line—where tribes could cross without passport or visa restrictions. Following the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in the 1970s, Pakistan experienced an influx of refugees fleeing violence and became host to one of the largest refugee populations in the world. Movement continued during the Taliban regime, and a second wave of forced movement occurred after the invasion of US-led coalition forces in Afghanistan from 2001–2005. At its peak, the number of registered Afghan refugees in Pakistan was estimated at 4 million. Non-Afghan refugees are from Somalia, Iran, and Iraq. See Table 1.

Click table to enlarge.

Despite hosting one of the world’s largest refugee populations for over 40 years, Pakistan is not party to the 1951 Refugee Convention and its 1967 Protocol and has not adopted any national refugee legislation. Since 2003, there has been reliance on a tripartite agreement between UNHCR, Pakistan, and Afghanistan that formally establishes voluntary repatriation as the durable solution for Afghan refugees. The timeline for return has been periodically extended, as return has been fraught with challenges.[24]

Afghan refugees in southwest Asia have experienced the world’s most protracted displacement. The majority of Afghan refugees live in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province (58%); 2% live in Islamabad Capital Territory.[25] Out of the registered refugees, 32% live in designated “refugee villages,” which are located primarily along the borders with Afghanistan in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Balochistan. The remaining 68% have long been settled in rural, urban, and peri-urban areas.[26] A large proportion of the Afghan population was born and raised as a second generation in Pakistan.

Out of the registered refugees, 39% are school-aged children between five to eighteen years of age.[27] Within the refugee villages, only 30% of the total school-aged children were enrolled in school.[28] This number drops further for refugee families settled elsewhere.

REGISTRATION AND REPATRIATION

A UNHCR-funded repatriation program for refugees was initiated in 2002, but conditions in Afghanistan were not conducive for voluntary return. Since then, there was an effort to document refugees and issue PoR cards, which temporarily provided the legal right to stay. PoR cards originally set to expire at the end of 2015 have been extended several times since then. In 2015, there was a greater push towards return from the Pakistani government, with revised incentives from UNHCR. The numbers of repatriating families have fallen in 2018.

As of June 2018, there were 1.4 million registered refugees in Pakistan (see Table 2). Unregistered refugees are still estimated to be between 600,000 to 1 million.

Table 2: Afghan Refugee Population in Pakistan since 2002

Source: UNHCR. Click table to enlarge

There was an additional drive for registration of undocumented families of Afghan origin in 2017 and for the issuing of Afghan Citizen cards. These help to protect cardholders from arbitrary arrest, detention, and deportation, and give the option of applying for visas to stay on as students or families. However, Afghan citizens are not considered “persons of interest” by UNHCR, as they are not categorized as seeking asylum but as having migrated for other reasons, e.g., livelihoods opportunities.[29]

In order to address the challenges that Pakistan was experiencing as a host country, from 2009 the government partnered with a Consortium of UN agencies to initiate the Refugee-Affected and Hosting Areas (RAHA) Programme. One goal of this program is to promote social cohesion and coexistence by addressing challenges such as access to livelihoods and education.

[24] Original tripartite agreement available here: https://www.refworld.org/docid/55e6a5324.html

[25] UNHCR Pakistan, “Mapping of Education Facilities.”

[26] Ibid.

[27] Ibid., 25.

[28] Ibid.

[29] From telephone conversation with UNHCR staff members Faisal Azam Khan and Uzma Irum, September 13, 2018.

APPENDIX C: REFUGEES IN ISLAMABAD

As the seat of the government and bureaucracy, Islamabad is not associated with any other provinces but exists as a federal territory. According to the 2017 census, Islamabad Capital Territory (ICT) houses a population of just over 2 million. It is often associated with the older city of Rawalpindi as a “twin city,” and the Islamabad-Rawalpindi metropolitan area is the third largest in Pakistan, with a population of more than 4 million.

Islamabad also has some of the fastest growing slums in the country, as informal settlements have grown in the absence of affordable housing. These are populated by ethnically diverse communities including rural migrants from Punjab province, Pakistani Pashtuns, and Afghan Pashtuns.

View of the grid pattern of Islamabad. Map imagery © OpenStreetMap 2019. Click map to enlarge.